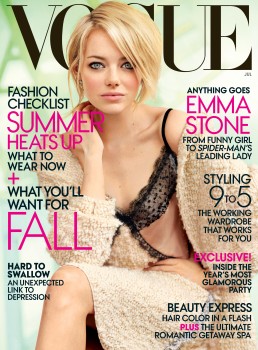

Vogue US July 2012 Non Scans Photos + Full Interview Transcript

When Emma Stone goes walking in New York, which she’s been doing a good deal in recent months, she keeps her head cocked toward her feet, like Schroeder from Peanuts, so that her blonde hair tumbles forward and obscures her face. At 23, Stone is at a transitional moment in her career, transforming from quirky comedienne to dazzling A-list star, and although it’s harder than it used to be for her to move along the sidewalk unnoticed, she has a New Yorker’s love for the odd, vibrant theatrics of urban life. One spring evening, I meet Stone at a wine bar in Hell’s Kitchen, and we walk up to the Alvin Ailey studio for a dance performance. (Stone, who spent much of her Arizona childhood studying dance, described it to me as “the most ultimately revelatory form of expression” besides movies.)

Clad in a knee-length black Madewell dress trimmed with white and wrapped in a gray DKNY coat, Stone, with her alabaster complexion and aqueous blue-green eyes, cuts a striking figure in the midtown foot traffic. When a man and a woman start arguing on West Fifty-fifth Street—“Are you trying to get me sent back to prison?” the afflicted gentleman cries—Stone keeps us halted at a green light, so she can hear how the dispute progresses. Her background is mainly in improv comedy, and her senses seem always on alert. At one point, Stone tells me she recently got a glimpse of Tilda Swinton. “It was like seeing a lion in a restaurant—you know what I mean?” she says. “She’s magnificent. Just looking at her feels like you’re imagining something.” It is not until we’re trying to find our seats in the theater that I’m reminded Stone has her own role to play. “Oh, my God,” our usher exclaims loudly, leading us up the aisle. “You look just like Emma Stone.” The actress grins nervously for a moment. “It’s weird, isn’t it?” she finally answers, and slips quietly into the last seat of the row. The usher’s eyes widen at her first word: Stone’s smoky voice is unmistakable. She’s had a lot of recognition of this kind lately. “The concept of movie star is something that you can never wrap your head around,” she says. “Not being a cog in a machine, there being guys in New York with cameras—it feels like it’s happening to a different person. That loss of anonymity, not being able to just sit and watch in certain circumstances, is very strange and very new.” It’s doubly strange because Stone is a watcher by temperament. If she weren’t an actor, she says, she would be a journalist—the two vocations share a goal of trying to figure out what makes characters “tick”—and it’s as a woman looking, rather than being looked at, that she seems most alive and engaged. Soon after we’re seated, she turns around to make a panoramic appraisal of the other guests. “Interesting audience,” she murmurs. Stone has a huddler’s style: When she talks to you, she moves in close, often with wry, sotto voce commentary on the surroundings, and within moments, you have built up such a catalog of private jokes (“Row H is ahead of the curve”), shared observations, and sniffle-giggling you almost feel you’ve known each other forever—a jokey intimacy that she has conjured effortlessly on-screen in movies from Easy A to last summer’s Crazy, Stupid, Love. “Oh, boy,” she exclaims with mock brio as the lights dim. “Here we go!” Stone has become a kind of celebrity ambassador, a highwattage movie star who nonetheless seems as if she might show up at your next dinner party, someone who sees what you see even as she scales the distant peaks of Hollywood fame. (“I probably scare some people when I meet them because I know most interviews that they’ve done, or what they’re like from interviews.”)

During an intermission, as we join the throng filing up the aisle, Stone swirls around to shoot me a mischievous look. “Did you see Katie Holmes with Suri?” she asks later. (I hadn’t, actually.) Then, with just a hint of dry irony, she adds, “Hollywood is moving east!” Stone’s low-key tendencies may prove hard to sustain in the coming months. This summer, she is making her first foray into the hot, effulgent spotlight of the international blockbuster: Just as Michelle Pfeiffer, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Kirsten Dunst once took their talents to the comic book–inspired box office (with career-boosting results), Stone is starring as the romantic lead of The Amazing Spider-Man, a $220 million, 3-D adaptation of the Marvel hero’s roof-dangling adventures, directed by Marc Webb. The film—with Andrew Garfield in the title role, and a cast that includes Martin Sheen, Denis Leary, and Rhys Ifans—arrives on a wave of fanboy allure and powerful publicity. (Stone and her costars went on their first global press tour in January, half a year before the opening.) And, according to delighted reports in the tabloids, the movie was also the birthplace of a real-life romance between Stone and Garfield—ensuring that its more intimate scenes will be close read for evidence of quickly beating hearts. “I thought it would be different in some way, acting in that kind of movie,” Stone tells me over sushi one evening at a small wood-paneled restaurant underneath the High Line. “It didn’t feel different, other than I did have to wear a harness and swing—Jesus Christ!—which I’d never done in anything else.” Stone plays Gwen Stacy, a brainy blonde who, in the original comics, was Peter Parker’s first great, haunting love. The film serves as a sort of origin myth, offering us a vision of Parker before his Mary Jane days. Yet Gwen is a fraught figure. Because her father is a police captain who is ambivalent about Spider-Man, she finds herself rapidly ensnared in her own web of guilt and mixed allegiances. In bringing the role of Gwen to the big screen, Webb was looking for someone who could convey the character’s complexity without weighing the dark story line down. Stone fit the bill—and more.

During the filming of onescene, in which Stacy is trying to keep her father (played by Leary) out of her bedroom, where she’s hiding Parker, Stone improvised a comic gambit in which her character claims to be laid up with cramps and forbids the older man to enter. “She invites other actors into these moments and she shakes them up,” says Webb, whose last feature was the indie hit (500) Days of Summer. “We were just lucky to get his reaction on-camera.” Her costar Garfield reports, “Working with Emma was like diving into a thrilling, twisting river and never holding on to the sides. From the start. To the end. Spontaneous. In the moment. Present. Terrifying. Vital. The only way acting with someone should be.” Webb says Stone’s knack for comedy made her a welcome counterpoise to Garfield’s more dramatic inclinations, too. “She could make him laugh,” Webb explains. “A lot of young actresses are either very serious and morose or they’re very doe-eyed and bat their eyelashes and are trained to seduce the camera. Emma sidesteps that.” Stone has become the go-to girl for strong, spunky characters bridging unreconciled worlds. In Judd Apatow’s Superbad, she played Jules, a cool, wry, party-throwing senior who takes two geeky boys (Jonah Hill and Michael Cera) more seriously than her peers; in Easy A, her first big lead role, she was a wisecracking teacher’s pet who runs with rumors about her sexual escapades. And in The Help, Stone’s first major break from comedy, she is the only character with enough gumption to reach out to the African-American domestics of sixties Mississippi. Each of these characters is, as she puts it, “going through some sort of transformation to be more of what they actually are.” And yet she says the similarity is unintentional. “There’s this Ryan Gosling quote that I steal all the time—I watched an interview with him in Cannes—and he said picking roles is like listening to songs on the radio: There can be a lot of really great songs in a row, but then one comes on that just makes you want to dance.”

An opportunity to work with actors she admires— “somebody who feels like they’re going to teach me a million things”—is frequently the start of Stone’s interest in a movie, and it’s led her to projects with Woody Harrelson (Zombieland), Octavia Spencer (The Help), and, of course, Andrew Garfield. Although she’s reticent about their relationship—Stone has never discussed her romantic life in public—she eagerly talks about his collaborative generosity. “As an actor, I learned a lot from working with Andrew, in terms of his approach and the way he works,” she says. “He’s incredibly giving.” As the characters she plays have grown more layered, Stone, too, has begun to take her craft more seriously. “It’s such a fun job, and it can be silly and light and about making people laugh,” she says. “I think I was doing it a disservice by thinking it’s not something ultimately important. I always was saying, ‘I’m not saving lives; I’m not a brain surgeon.’ And that’s true—I’m not saving anyone from any life-threatening illnesses. But I get to tell stories, and that’s a pretty important task.” For years, Stone liked to tell people that she was a hammy kid long destined for a life in theater; it’s only recently she’s realized this is totally untrue. “I thought I was song and dance–y, and jazz hand–y, and then I realized I wasn’t, really, before I was eleven. I was a really anxious kid,” she says. Growing up in Scottsdale, Arizona, Stone had her first panic attack at eight and spent the next few years in therapy, burrowed underground. “I was just kind of immobilized by it. I didn’t want to go to my friends’ houses or hang out with anybody, and nobody really understood.” It wasn’t until she turned eleven that she started to emerge, helped along by comic theater: Onstage, she realized, she could escape from her anxious thoughts and turn outward. “It gave me a sense of purpose. I wanted to make people laugh,” she explains. “Comedy was my sport. It taught me how to roll with the punches. Failure is the exact same as success when it comes to comedy because it just keeps coming. It never stops.” At twelve, Stone flew from Scottsdale to Los Angeles to audition for the Nickelodeon show All That. She hated the place and vowed never to make her life there. Just two years later, though, Stone was doodling in her sixth-period history class when she had an epiphany: She wanted to be a movie actor, and she would need to be in L.A. to make it happen. At the end of the school day, on an impulse that has since become part of her lore, she rushed home and made a PowerPoint presentation to convince her parents. “It was just the fastest way of doing it,” she says. “I wasn’t very good at cutting things out and pasting.” Stone’s father is a contractor; her mother kept up the household. Stone jokes that they must have been insane to let a high school freshman drop out of classes to follow one of the most hackneyed dreams in the book. But when her brother, two years younger, became a star high school quarterback, their father, who had played through college, set up a 40-yard football field in the backyard. For the next three years, Stone (her real name is Emily; she registered as Emma with the Screen Actors Guild to avoid a duplication) lived with her mother in California. While auditioning for roles, she was home-schooled—in philosophy, psychology, journalism, and sign language to fulfill her foreign-language requirement.

Once, for ascreenwriting assignment, she wrote an episode of Mad About You, the nineties sitcom, in which Paul Reiser’s character encountered his idol, Paul McCartney. “It was called ‘The Pauls,’ ” she says. “They met each other and hilarity ensued—or was supposed to ensue.” “The Pauls” remains Stone’s only screenwriting effort, but it was not her last brush with Pauldom: In 2009, while filming Zombieland, she met McCartney and later persuaded the Beatle to draw her two blackbird feet, in honor of her mother’s favorite song; the entire Stone family had his design tattooed on their wrists to commemorate her mother’s overcoming the rare and aggressive breast cancer known as triple-negative. “She really went through the wringer with that one,” she says. Stone’s first break famously came when she dyed her hair brown—she’s naturally blonde—and auditioned for Superbad. “I got a call one day from Judd. He said, ‘We found the girl,’ ” says Matt Tolmach, who was then at Columbia Pictures and is now a Spider-Man producer. “She came in to see me, and what I got is exactly what you get in that movie when Jonah meets her: She’s as funny as or funnier than you are; she’s so quick; she’s stunning, so she’s disarming; and she’s just cool. You’ll say anything to her because you just want her to be your best friend.” Since then, Stone has realized many of her childhood ambitions, including hosting Saturday Night Live. (She’s done it twice, pioneering such skits as “Les Jeunes de Paris,” wherein a cadre of somber youths dance spasmodically to Europop.)

On talk shows, she is quick and witty, a strength she attributes to her early background in improv. Many of Stone’s most important decisions have an improvised air. In 2009, she was sitting in the Little Door, a restaurant in west L.A., when suddenly, as swiftly as she’d had the urge to move to Hollywood, she wanted out. “It was so nice, and it was so beautiful, and to my right there was someone talking about a script they were working on, and to my left someone was talking about a movie they were producing. And I wasn’t working. And I just thought, If these are the only conversations I hear when I’m eavesdropping, how can I possibly know what it’s like to live a regular life?” She’s lived in New York since. Stone still gets panic attacks—she had one on the set of Crazy, Stupid, Love., as Ryan Gosling hoisted her up for their now-iconic Dirty Dancing lift. To cope during the filming of Spider-Man, she ramped up her interest in baking. “I think I felt really out of control of my surroundings,” she explains. “I was just baking all the time. There were stacks of things in the kitchen that nobody could possibly go through. It seemed like it made me feel, if I put these in, I’ll know what the outcome is. . . . I was overbaking.” Increasingly, though, she’s tried to glean creative strength from her anxiety. Stone’s first forays into drama, with The Help, the 1940s thriller Gangster Squad (another Gosling collaboration, directed by Zombieland’s Ruben Fleischer and opening this fall), and even Spider-Man, have forced her to confront feelings that she spent much of her life trying to hide. It hurts, she’s found, without laughter to break the mood. “Comedy is really vulnerable, but the second something falls flat, you”—she snaps her fingers—“you pick up and continue. You’re flashing skin for little seconds. Whereas you’re totally naked in something that isn’t funny.

There was a day like that on Spider-Man, where Andrew and I were sitting on the floor, and there was a scene in my bedroom, and it was just the two of us, and it was an incredible feeling. It’s something I’d like to keep experiencing and understanding how to maneuver, in my life as well as in the script—you know? How to live in that place without making a joke.” One evening, a couple of days later, I visit the TimesCenter to see Stone voice the role of Fran Kubelik in The Apartment, opposite Paul Rudd—part of a series of table readings of classic screenplays that the director Jason Reitman has been organizing. Stone spent part of the week rewatching the 1960 Billy Wilder film, fretting about how she would compare with Shirley MacLaine. When she appears, though, in a simple black blouse and jeans, with scarlet lipstick and her hair drawn up into a loose approximation of a pixie cut, she seems to recall not just MacLaine’s Miss Kubelik but a movie star of that vintage. It’s as if she has absorbed the glow of that cinematic era and projected it back outward, along a different trajectory, replacing MacLaine’s jocularity with a less guarded mien, as if to underscore the script’s garish machismo. Later, she tells me she was shaking through the entire reading. Like MacLaine, whose leading ladies always had a layer of whimsy, Stone seems to be cultivating a Hollywood persona all her own. The lodestars of her creative life are Diane Keaton, Gilda Radner, and the Charlie Chaplin of City Lights: performers who ducked traditional measures of glamour to build a style on their truest and most antic selves. “I never really wanted to dress like anyone—well, that’s not true. I probably wanted to dress like Diane Keaton, but that’s just because I love her so much,” she says. “She’s really herself, and that’s what I like.” Inspired by Keaton’s seventies style, she leans toward an unaffected, menswear-infused wardrobe in everyday life. In more refined company, she favors the work of designers known both for their simplifying eye and for their embrace of risk.

When Stone first donned Alber Elbaz’s belted, floor-length Lanvin gown for the 2011 BAFTAs, she had a revelation: “It was a red dress, it was asymmetrical, and the minute I put it on I thought, Oh, this is what fashion does for people. It makes them feel like it’s an extension of themselves.” Stone has returned to Elbaz’s designs for several highprofile occasions—including the most recent Met gala, at which she wore a red Lanvin frock covered in sprightly crystal florettes. “The best thing about dressing her is that she never disappears in the clothes,” Elbaz told me recently over the phone from Paris. “It’s always Emma wearing the dress—the dress never wears her.” For her debut on the Oscar stage in February, Stone chose a capricious bow-studded raspberry gown by Giambattista Valli, who describes her sensibility as “a new idea of femininity.” With help from the SNL comedy writer John Mulaney, Stone and Ben Stiller worked up a routine in which she played a wide-eyed Hollywood newcomer—a role that, after all, isn’t too far from reality. If you ask Emma Stone about her plans going forward, you will get a range of ideas, crossing several disciplines and corresponding to various lives that she’s watched and found, in some sense, fascinating. Visiting the Salk Institute in the course of filming Spider-Man made her realize how interesting she finds biology and how little she knows about it—which in turn made her wonder whether she should take some of the college classes she missed out on. She’d love to return to the stage, she says (Garfield appeared on Broadway this spring in Death of a Salesman), if her voice could withstand the performance schedule. (Stone’s smoky timbre comes from vocal-cord nodules.) For the moment, though, she’s enjoying the opportunities at hand. “She’s trained herself to put people at ease, on- and off-camera,” Marc Webb says. “She’s someone who’s going to be around for a while.”

Thank you too @surprisecenter <33333333

Етикети:

photos: photoshoots

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(

Atom

)

No comments:

Post a Comment